ABOUT HVALDIMIR

The “Russian Spy” Whale

Hvaldimir’s Arrival in Norway April 2019

Hvaldimir was discovered in Norwegian waters in April 2019, near the island of Ingøya in Måsøy municipality. This region is at the northern tip of the country, approximately 300 km (via seafaring vessel) from the Norwegian/Russian maritime border. Hvaldimir was first photographed wearing a webbing harness with what appeared to be a mount for a small camera. Once that harness was removed, writing on the buckle stating “Equipment St. Petersburg” in English was observed. Hvaldimir was very interested in people and responded to hand signals. Based on these observations, it appeared as if Hvaldimir arrived in Norway by crossing over from Russian waters, where it is presumed he was held in captivity.

Fig 1. Buckle of the harness that Hvaldimir was wearing. Allan Klo/NRK

Fig 2. Hvaldimir in his harness, 2019. Håvard Hesten

Hvaldimir when he entered Norway in 2019 and the presumed area he came from in Russia. BBC News

We don’t know what his life in captivity involved, but there have been a number of different scenarios proposed, from him being the therapy whale named “Semyon,” to his life in the military under Russian control. When looking at the latter and adding observations of a camera mount on his harness, the idea was proposed in the media that Hvaldimir may have been a “Russian Spy.”

2008 video of “Semyon,” the therapy beluga whale who Hvaldimir has been proposed to be. Morten Vikeby

Fig 3. Photo showcases whale pens and the military base where it has been proposed Hvaldimir came from. BBC

At this stage, we don’t know Hvaldmir’s early history with certainty, and there has been a lack of conclusive evidence to indicate exactly what his life entailed prior to entering Norway.

There are many unanswered questions:

For example, was he captured from the wild or born in captivity?

If he was taken from his family in the wild, where did that happen and how old was he?

Could his mother have been captured with him, and is she still alive and held in captivity today?

Hvaldimir’s Early Time in Norway

After his arrival and the removal of his harness, Hvaldimir became a semi-permanent resident of the town of Hammerfest, above the Arctic Circle in northern Norway for a period of approximately three months. During this time, he was observed in poor condition and attempts were made to manage his care through provisioning (feeding) by Norwegian Orca Survey. After some time monitoring his condition and feeding behaviors, it was noted that Hvaldimir hunted and found available prey on his own. Hvaldimir left Hammerfest in July 2019.

Over the following years, Hvaldimir began slowly transiting along the Norwegian coastline, primarily southbound. Although he has been documented feeding entirely on his own, Hvaldimir has continued to actively seek out human presence and aquaculture activities, spending a majority of his time at fish farm facilities.

Fig 4. Pictures of beluga whale ‘Hvaldimir’ in summer 2019; (A–C) Photos show observations of his body condition when in Hammerfest between May and July 2019; (D) with the back-mounted, suction cup attachedGoPro video camera used to record foraging behavior; (E) being hand-fed herring during a routine feeding session; and (F) in the harbor of Hammerfest, northern Norway, in July 2019, playful and seeking human contact. (PDF) Feces DNA analyses track the rehabilitation of a free-ranging beluga whale. Available from the following link.

Guenther, Babett & Jourdain, Eve & Rubincam, Lindsay & Karoliussen, Richard & Cox, Sam & Haond, Sophie. (2022). Feces DNA analyses track the rehabilitation of a free-ranging beluga whale. Scientific Reports. 12. 6412. 10.1038/s41598-022-09285-8.

Viral video of Hvaldimir playing with World Cup rugby ball.

Viral video of Hvaldimir returning a phone that dfropped in the water.

Time Spent at Fish Farms

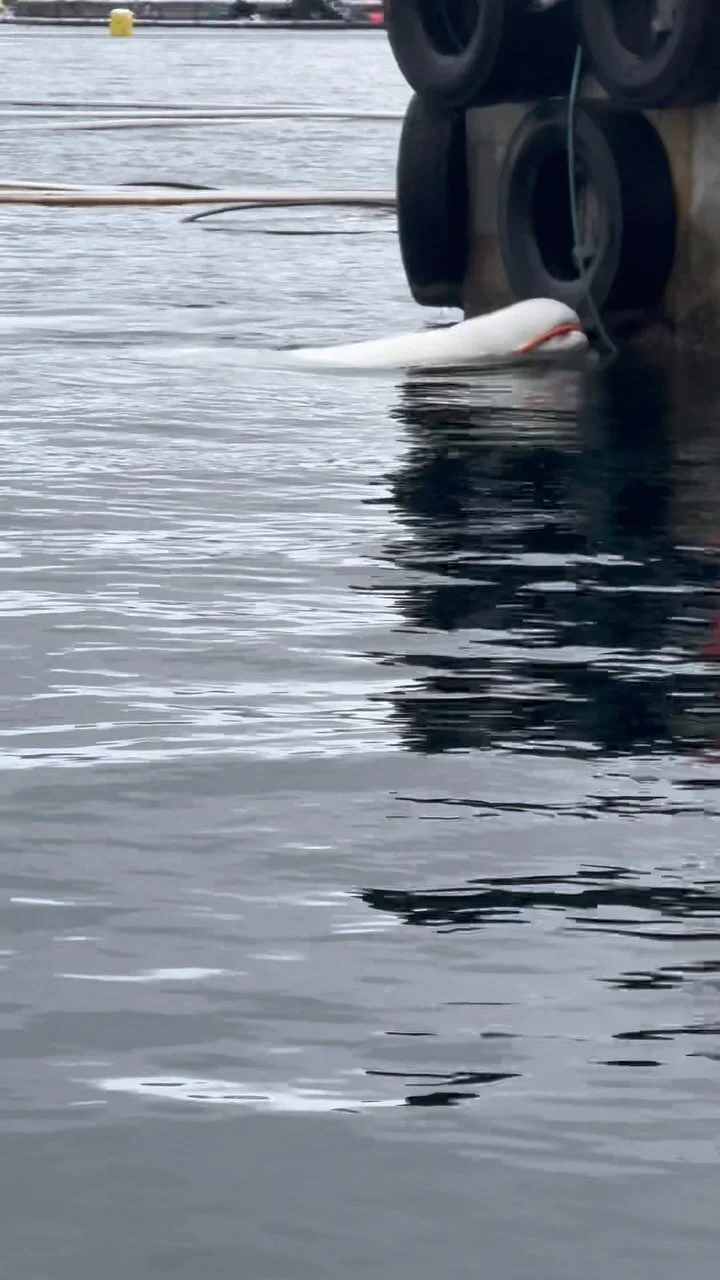

Hvaldimir has been observed moving from one fish farm to another over the years he has resided in Norway (you can view his previous activity on a map, below). He routinely followed the catamarans both within the aquaculture facility boundaries, and furthermore followed these vessels to their respective land-based stations. While vessels were docked and not in operation, he was often observed “logging” in between the hulls of the vessels. Hvaldimir has also been documented actively feeding at the farms; wild fish congregate underneath the nets, and this could serve as a stable, familiar area for him to find available prey.

It is impossible to determine with certainty why he spent a majority of his time at industrial fish farms, though theories pose several questions:

Could it be that he had learned of ample prey available for him to hunt?

Were catamarans or similar vessels used at the facility where he was presumably held in captivity?

Does this pattern provide him with a familiar routine or a sense of comfort?

Was he looking for mental stimuli and predictable repeated interactions as a solitary individual?

Fig 5. Marine Mind’s Location Data of Hvaldimir’s movements between 2019—2023.

Injuries & Resilience

A closer look reveals that Hvaldimir has not been free from accidents associated with human interactions. He has been struck by boats multiple times, the scars of which can still be seen clearly today. Life as a solitary sociable individual places Hvaldimir at a statistically significantly higher risk, as such animals often struggle to survive beyond a few years. Injuries resulting from boat collisions, entanglement in fishing gear, and human-transmitted pathogens are all elevated threats for any marine mammal in constant, close proximity to humans.

While the threats he faced were very real, our field team had observed resilience and adaptability by Hvaldimir. Cetaceans (whales, dolphins, and porpoises) are very intelligent animals, capable of adapting to a variety of environmental situations. The majority of significant injuries sustained by Hvaldimir happened when he first arrived in Norway, this could be a sign he was learning from negative experience and this has potentially resulted in behavioral adaptations.

Fig 6. June 2020 Fabrice Schnoller/ SOSF

Fig 7. July 2020 The Orca Channel

Fig 8. September 2020 The Orca Channel

Figures 6—8 above showcase Hvaldimir’s most significant injury since entering Norway. It is unclear how the injury occurred, and was over one meter in length. Due to supervision by Norwegian Orca Survey and international veterinarian experts, he successfully healed, and the scar can still be seen today. Screenshots taken from The Orca Channel’s documentary, “A Tale of a Whale - Hvaldimir's Journey in Norway.” Link to this video can be seen by clicking on any of the above images.

Capture of Wild Beluga in Russia

Capturing cetaceans for various purposes has a long history, although sources are scarce. For the beluga specifically, captures date back to the 1860’s for entertainment purposes in North America. There have been a number of locations where beluga whales have been taken from the wild, including the White Sea in northern Russia, approximately 1,100 km from where Hvaldimir was discovered in Norway. Near that region, in Kola Bay, to the north of Murmansk, it is possible to see holding pens for beluga, using tools such as Google Earth.

An alternative narrative, which has been presented by multiple sources, suggests that Hvaldimir may have been captured from the Sea of Okhotsk, which is in the Russian Far East and lies between Russia and Japan. There have been many instances of beluga being taken from this region, including in 2018, when 87 beluga and 10 orca were taken from the wild and held in the “Whale Jail” at Srednyaya Bay.

Today, it is estimated that more than 300 belugas live in captivity worldwide.

Russian Whale Jail in Srednyaya Bay, 2018. Video courtesy of OceanX.

Fig 9. Google Map image showing locations of the Sea of Okhotsk and the White Sea where Hvaldimir could have been taken from the wild; Ingøya, Norway where Hvaldimir originally appeared in 2019; and GPS coordinates for a known marine mammal program run by the Russian Navy (near Murmansk, Russia).

Historic Use of Cetaceans for the Military

There are examples of working cetaceans in current history, specifically as part of military assignment. The most notable and robust programs have come out of the United States and Russia. The live-capture of marine mammals including sea lions, beluga and bottlenose dolphins began in the US in 1959 as a path for research; specifically, a dolphin’s echolocation and streamlined anatomy for the development of weapons. Russia followed suit within a few years, and both programs quickly evolved after observing that dolphins were highly amenable.

Marine mammals have been trained to deliver supplies to divers, locate objects, guard boats, and partake in underwater surveillance using camera equipment. In 1975 the exploration to use belugas for military use began in the United States. Between 1977 and 1980 six beluga were captured by the US-based Naval Ocean System Center for military research in Churchill, Canada. The proposal of using beluga whales stemmed from their adaptations, as they are accustomed to colder, Arctic temperatures and can dive deeper than bottlenose dolphins. In the early 1980’s, a military aquarium was established in Vityaz Bay (Russia), which also focused on beluga whales and other marine mammals.

Both programs are still in operation today, although the US no longer live-captures marine mammals for its program. Russia, on the other hand, still captures marine mammals for military use, and currently has belugas as part of this program. We know that belugas are held in Kola Bay, to the north of Murmansk, although their training and use with the military is still unclear.

The most recent example of marine mammals being used in wartime activities has been the deployment of Russian-trained military dolphins to occupied Sevastapol, Crimea in 2018. There, they have remained during the Russo-Ukranian War.

Video released by the US Navy in 1964 about the Marine Mammal Program. Naval History and Heritage Command, Photographic Section UMO-26.

Modern video released by the Naval Information Warfare Center, Pacific (NIWCP) on the current status of the US Marine Mammal Program.

A Solitary Sociable Cetacean

Beluga are typically found in groups and are social in nature, forming social structures that most commonly comprise between 2-10 individuals, or upwards of 2,000 or more. Hvaldimir has been separated from others of his own species since before his arrival in Norway in 2019, and is classified as a Solitary Sociable Cetacean (SSC); individuals separated from others of their own species who are typically social in nature, living in close proximity to people, and either seeking out or being sought out by humans. We do not know how long it had been since Hvaldimir had interacted with another of his own species.

Fig 9. Wild pod of belugas.

Fig 10. Hvaldimir resting in a Norwegian fjord.

The Tale of “Aydin”

There are many other documented cases of SSC’s in recent history, although very few were formerly captive, nor have they exhibited behavior similar to Hvaldimir.

The closest example of such incidents that we can reference dates back to September 1991, a case that involved a captive beluga who was held in a sea pen at Biotechnical Systems Institute in Sevastopol, Crimea, then under Soviet Union military control. The base reportedly housed several trained marine mammals, including dolphins, sea lions, and two beluga. A September storm damaged one of the enclosures, and the beluga “Tichka,” swam away. He had been taken from the wild at approximately three years old and given “primary training.”

On January 27th, 1992, approximately four months after his escape, Tichka was observed 350 km south near a harbor in Gerze, Turkey. At that time, he was noted as being thin and seeking out fishing vessels. Tichka appeared to seek out human interaction and responded to hand signals. Because his history prior to entering Gerze was unknown, the town gave him a new nickname, “Aydin.”

Fig 11. Aydin, or Tichka, showing the scar on his upper right lip. From A Farewell to Whales by Pierre Béland.

Fig 12. Aydin being fed by divers in Gerze, Turkey. From A Farewell to Whales by Pierre Béland.

Fig 13. Aydin being fed a fish. You can see his worn-down teeth. From A Farewell to Whales by Pierre Béland.

Many questions were raised by local authorities as to where he came from. Simultaneously, Russian authorities did not admit or deny having any connection to the whale. Aydin was monitored for some time by two Canadians, beluga expert Pierre Béland and veterinary pathologist Dr. Sylvian De Guise, who later recommended that the beluga be left where he was. They observed Aydin’s teeth worn down to the gums (similar to Hvaldimir). Due to some of his trained behaviors, the media perpetuated that he was trained as a saboteur.

The Turkish government gave Russia the authority to recapture Aydin, although locals in Gerze protested. By early April 1992, Aydin was recaptured and was once again under Russian control. It was later discovered by the Associated Press that Aydin was performing under the name “Kirill” at an oceanarium in Lapsi, Ukraine.

Fig 14. Aydin being recaptured. From Into the Blue by Virginia McKenna/Daily Mail

Fig 15. Aydin with Igor at the Lapsi oceanarium, 1992. Emilio Nessi

In November 1992, another storm hit, and Aydin escaped the enclosure, again. In February 1993, Aydin returned to Gerze, Turkey. The Turkish Minister of Environment denied any recapture attempt, and Aydin remained near Gerze for the following five months, being fed by divers and visited by tourists. By mid-July 1993, Aydin disappeared, with no conclusive evidence as to what became of him.

While there are many other instances of cetaceans seeking out humans, the above illustrates the most similar, in terms of species, potential background, and behavior to Hvaldimir.

Our Team

At Marine Mind, we have a diverse team and an experienced advisory board, many of whom have been involved in Hvaldimir’s protection since the inception of these efforts. Our CEO, Sebastian, has worked closely with Hvaldimir since 2021. Our organization forms a multidisciplinary group encompassing experts ranging from marine mammal veterinarians to wild cetacean researchers, biologists, and educators. In the field, our team works to better understand Hvaldimir and his situation, whilst educating the people we encounter about marine life and its significance to humanity.

Our mission was to help reduce human-induced threats, increasing Hvaldimir’s prospects of living a long and fulfilling life. Unlike most solitary sociables who have left their wild societies, Hvaldimir’s solitude was not necessarily by choice. He may have lacked the knowledge of how and where to reunite with his kin. Our aim was to assist him if and when needed.

Meet Our Team

Our Approach

Our field team remained near Hvaldimir’s location, serving as a readily available resource for beneficial interventions. We maintained communication with aquaculture workers who shared most of their days with Hvaldimir, offering assistance to divert his attention away from disrupting critical tasks, preventing him from being perceived as a nuisance. While we were careful not to draw tourism towards Hvaldimir, much of our activities revolved around engaging with visitors through sharing safety tips on how to act when encountering marine mammals and providing exciting knowledge to enhance people’s understanding of whales.

Our local team consistently observed and documented his behavior and activities in the field. We regularly shared this information with our board of advisors and other experts in order to have a broad knowledge of Hvaldimir's unique behavior. By doing so, we can help other solitary cetaceans and further our understanding of marine mammals.

Fig 16. Hvaldimir just beneath the surface.

Fig 17. Hvaldimir resting in a Norwegian fjord.

Hvaldimir’s Impact

Hvaldimir has been met by thousands of people, and has over time become well known both locally and internationally. His presence granted a rare opportunity to inspire a shift in the way people perceive cetaceans. It also offered an excellent avenue for research to enhance our understanding of individuals in similar situations and how we can better ensure their well-being.

A majority of visitors to Hvaldimir’s locations were children. Since 2019, Hvaldimir has been an inspiration to thousands of children in both Norway and Sweden, not including his international impact through the distribution of his story in the global media. By meeting a beluga, who otherwise would not inhabit our Norwegian coastal waters, the youth of this country now have a core memory of an incredible marine mammal. This experience alone has the possibility to inspire passion for and the conservation of our oceans for future generations.

Video of Hvaldimir bringing our on-site team a piece of seaweed.

The Results

By closely monitoring Hvaldimir and increasing awareness and understanding of his situation, Marine Mind diminished interactions that could lead to harm. Such incidents could include provisioning (feeding) by humans, reckless swimming, overcrowding of motor vessels and interacting with Hvaldimir with potentially damaging objects.

Aquaculture personnel knew that our team was available if needed, which prevented frustration when Hvaldimir engaged with objects at inopportune times. Moreover, providing knowledge about the animal and his known behavior helped alleviate concerns about more serious incidents.

Educating visitors and implementing our traveling school program ensured that a diverse and extensive audience had the opportunity to learn more about marine mammals and the ocean. Through these efforts, we aspire to instill a greater sense of animal welfare and climate-conscious decision-making among current and future leaders.

The opportunity to study Hvaldimir has provided valuable insights into Solitary Sociable Cetaceans. Sharing the behaviors and findings we observed contributes to a better understanding of the inner workings of a species about which there is still much to learn.

Fig 18. Sebastian presenting to a local school.

Fig 19. Hvaldimir approaching our on-site team.

The Task Ahead

There have been many suggestions made by the public, local governments, and world-renowned scientists on how to potentially ensure Hvaldimir’s safety. One suggestion has been to relocate him to the Arctic for the possibility of reuniting with others of his own species, or to transfer him to a coastal sanctuary for rehabilitation and eventual release.

At Marine Mind, we are committed to transparency. While we have a dedicated Board of Advisors that include top-experts in their respective fields and an on-site team dedicated to education and protection, the answer of what to do next is ever-evolving.

Some of the questions we have to ask ourselves include the following:

What population stock did Hvaldimir come from?

If Hvaldimir was indeed taken from the wild, where would be the best place for his relocation, genetically?

Would he fit into beluga social structures, or would he end up seeking out human interaction in coastal waters (potentially in Russia) once more?

Could he be re-captured if he travels to Russia and exhibits these behaviors?

If he came across wild beluga, would they integrate him into their society?

Was Hvaldimir born in captivity?

If so, does he want to see others of his own species?

If relocated to the Arctic, would he have the knowledge to navigate through sea ice?

Would he follow the migration of his kin?

Because he is reliant on the Norwegian aquaculture industry, potentially for the abundance of wild fish congregating under the nets in those areas, would he have the ability to predate on fish in the Arctic?

These are just a few of the questions we are constantly asking ourselves, and truthfully, we will never know all the answers. We strive to learn from Hvaldimir, take the advice of experts in our global community, and continuously change with the more information we gather on his current and past situations.

Want to Learn More?

For current updates, we highly suggest following us on social media as we post regularly and update our community with the insights we continue to glean from his situation.